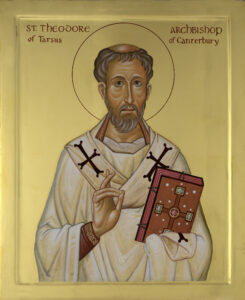

Our Mission is dedicated to the patronage of St Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury. For us, St Theodore represents the indissoluble link between the Eastern and Western Churches, for he was himself a Greek, hailing from the same Anatolian city as St Paul — Tarsus — later fleeing to Constantinople when Tarsus was invaded by the Persians. The Troparion and Kontakion of his feast, celebrated on 19 September, are testimony to St Theodore’s immense contribution to the English Church after Pope Vitalian consecrated him Archbishop of Canterbury:

As a compatriot of the preëminent Paul and a scion of Tarsus, O Theodore, bestowed upon the West by God you did traverse afar, proclaiming the peerless Gospel of Christ among the Angles and Saxons. Wherefore, having received you as a gift divine and great, we cry out in thanksgiving to the Lord on high: Truly wondrous are You, O Saviour, in Your holy bishop and in all the saints!

As primate of the English Church you tended well your spiritual flock, repelling the assaults of the spiritual wolf with the sling of the Orthodox Faith and the staff of sound doctrine. Wherefore, we ever cry out to you, O Theodore, gift of God: Glory to Him Who has given you strength! Glory to Him Who has crowned you! Glory to Him Who works healings for all through you!

The story of how St Theodore came to be Archbishop of Canterbury is relayed below.

In the year 666 King Oswy of Northumbria talked over with the King of Kent methods of drawing closer the northern and southern Churches [of England], which needed to be done now that the Council of Whitby (664) had reached agreement on matters in dispute between the two Churches. They decided that the Archbishopric of Canterbury, which had once been the most important in Britain, but which had lost much of its prestige as a result of the work of St Aidan at Lindisfarne, should again be made preëminent. They therefore chose a certain Wighard as Archbishop, and sent him to Rome to be consecrated by the Pope. Wighard died, however, almost as soon as he reached Rome, and the Pope therefore considered whom he should choose to take his place. He offered the post to Hadrian, the African abbot of a monastery near Naples, but Hadrian refused, at the same time recommending Theodore, a man of sixty-six years of age. Theodore was a Greek, born in Tarsus, the city of St Paul, who had studied in Athens and was learned in Latin and Greek, in literature and philosophy. The Pope consecrated Theodore as Archbishop, but asked Hadrian to go with him and help him.

Theodore set out, and arrived in Canterbury in 669. At that time the Church in England was hardly organized at all. Each of the missionaries had worked independently of the others, while the dioceses of the bishops were very large, and corresponded to the kingdoms into which Britain was then divided. This meant that the boundaries of the dioceses varied as the continual wars caused the kingdoms to change in size. In addition, though the Council of Whitby had settled the differences between the Churches founded by St Augustine and by St Columba, many of the bishops and monks had not yet settled to the new ways.

Theodore started on a tour round England. He found bishoprics empty and made new ones; he reconsecrated St Chad because he had not been properly made a bishop, and he let it be generally seen that the Archbishop of Canterbury was in charge of the whole Church. Then he set up schools at Canterbury for teaching not only religion, but also Latin, Greek, music, astronomy and medicine; he and Hadrian both taught personally in these schools, till Canterbury became known as a place where learning was loved.

In 673 he held a synod or conference of bishops at Hertford. This had not been done before, and it marked another step forward in the efficient organization of the Church. Many think that this synod was the first of those representative meetings out of which grew our present Parliament. Here he began a policy of subdividing the big bishoprics, and basing dioceses not on kingdoms, but on the land occupied by different tribes and peoples.

Theodore died when he was eighty-eight. He was a gentle and affectionate man, but he is remembered chiefly because he was a good organizer of men. Just as hermits like Cuthbert, missionaries like Aidan and men of prayer and inspiration like Columba are needed in the Church, so also are men like Theodore, who carry successfully upon their shoulders a great weight of organization and responsiblity.