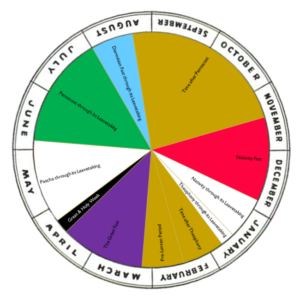

Our Calendar

Our Mission follows the Byzantine liturgical calendar — that of the Great Church of Constantinople-New Rome — with local variations as celebrated by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, to which we belong. The Byzantine calendar, while celebrating many of the same great feasts as the Roman calendar, is nonetheless considerably different in detail. For example, the Church Year begins not at Advent but at the Indiction of 1 September (the old Byzantine new year) while Advent itself — known as the Nativity Fast — lasts 40 days rather than four Sundays. There are several more fasting periods throughout the year, such as the Dormition Fast two weeks before the Dormition (Assumption), the Apostles’ Fast between the second Sunday after Pentecost and the feast of Saints Peter & Paul and, of course, the Great Fast of Lent, which begins two days earlier than in the West. But, while Pascha (Easter), the Nativity of the Lord (Christmas), the Dormition, the feast of Saints Peter & Paul and many more feasts are celebrated on the same nominal days as in the West, others vary. For example, All Saints’ Day is celebrated on the second Sunday after Pentecost, while there are five Saturdays of All Souls served throughout the Church Year.

Twelve Great Feasts (and five more)

After Pascha, the feast of feasts, there are twelve more days which are of especial importance in the Byzantine calendar. Often these are depicted on an upper row of a church’s iconostas (icon screen). They are: the Nativity of the Theotokos (8 September); the Exaltation of the Cross (12 September); the Entrance of the Theotokos in the Temple (21 November); the Nativity of the Lord (25 December); Theophany (6 January); the Entrance of the Lord in the Temple (2 February); the Annunciation (25 March); the Entry into Jerusalem (Sunday before Pascha); the Ascension (forty days after Pascha); Pentecost (fifty days after Pascha); the Transfiguration (6 August); and the Dormition of the Theotokos (14 August). In Ukraine, the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos (1 October) is also given precedence just behind the twelve great feasts, and is celebrated on the same day as the Defenders of Ukraine. Other great feasts not listed among the twelve are the Circumcision of the Lord (1 January); the Nativity of Holy John the Forerunner (24 June); the Feast of Saints Peter & Paul (29 June) and the Beheading of Holy John the Forerunner (29 August).

Thirteen days behind no more

Until 1 September 2023, the Mission used the old Julian calendar rather than the Gregorian calendar to calculate its liturgical year; this was in common with the Greek Catholic and Orthodox Churches in Ukraine. This meant that all liturgical dates occurred 13 days after the corresponding civil dates. So, for example, while the Nativity of the Lord is always celebrated on 25 December, the old Julian calendar calculates 25 December to fall on what we know as 7 January. This is also why ‘Orthodox Easter’ is usually celebrated on a different date to that in the West — because the starting point for the calculation of Easter, 21 March, actually falls on 3 April in the old Julian calendar.

But why?

The old Julian calendar was introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BC and continued to be used in the West for more than 1,600 years until the more accurate Gregorian calendar we use today was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 (though this ‘Papist Calendar’ continued to be resisted in Britain until 1752!). While Caesar’s calendar, designed by Greek mathematicians and astronomers, was far more accurate than that which preceded it, its calculation of the length of the solar year as lasting 365.25 days (observed in a cycle of 365 days for three years and 366 for the fourth) overshot the length of the astronomical solar year by 11 minutes, causing it to fall behind by one day every 128 years. This is why the calendar is currently 13 days behind and will be 14 days behind by 2100.

For some, being out of sync with the secular world comes as a benefit, particularly with regard to the frenzy of commercialization around Christmas and Easter in modern times. However, the Church Year has been designed to honour God’s Creation by following its rhythms and cycles, sanctifying them with a rich spiritual significance. This is why Pascha is calculated from the vernal equinox — after which there are more hours of light than darkness — and why the Nativity falls nine months later (specifically, nine months after the feast of the Annunciation on 25 March, which was believed to be the date of the vernal equinox in 46 BC) only a few days after the winter solstice — the shortest day — which symbolizes the darkness before the dawn. These celestial phenomena herald the Incarnation and the Resurrection, the birth and rebirth of the Light, the twin axes on which the entire Christian calendar spins. The further the liturgical calendar drifts away from them, the weaker their mystical symbolism becomes.

Why did this change?

There has long been debate over the accuracy of the Julian calendar in the East. Indeed, Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremias II considered adopting the Gregorian calendar in the sixteenth century but ultimately rejected it. The increasing inadequacy of the calendar was again raised at the Pan-Orthodox Council of Constantinople of 1923, however, and the ‘revised’ Julian calendar was adopted by most of the Greek Churches. This revision of the Julian calendar is actually more accurate than the Gregorian calendar, which will fall one day behind on 29 February 2800. The calendar was originally proposed with a purely astronomical calculation for the date of Pascha — the Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, observed from the meridian of Jerusalem — but a lack of consensus meant a compromise was reached: those who wished to adopt the new calendar could do so for the fixed feasts of the solar year, but Pascha and its moveable feasts would be celebrated by all according to the old.

The Patriarchate of Moscow, then headed by Patriarch Tikhon, initially agreed to adopt the new calendar — but the chaos ensuing from the Bolsheviks’ severe persecution of the Church, in which Tikhon himself would be martyred, meant this was never enacted. The Orthodox Metropolis of Kyïv was at that time administered by the Patriarchate of Moscow and, consequently, remained on the Julian calendar. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, despite being in communion with Rome since 1596, also chose to remain on the commonly-accepted Julian calendar.

In February 2023, a year into Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine, both the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (autocephalous since 2019) announced they would switch to the revised Julian calendar from 1 September. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Eparchy of the Holy Family, to which we belong, opted to go a step further and adopt the Gregorian calendar in its entirety, including the celebration of Pascha/Easter, which in 2024 will take place on 31 March.

In 2025, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches will both celebrate Pascha on the same date. This happens periodically when the Gregorian and Julian calculations happen to coïncide. Pope Francis and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew are both enthusiastic about reaching agreement on a common date by this point, and have recently reiterated this desire. The astronomical calculation proposed in 1923, and subsequently adopted by the World Council of Churches in 1997, could be a contender for this common date, being as it is the most literal implementation of the Nicæan formula. However, it remains to be seen whether such agreement will come to fruition.

Further Reading

For more information, see Easter, Calendar and Cosmos: an Orthodox View by Father Andrew Louth and Towards a Common Date for Easter by the World Council of Churches.