Christ — Our Pascha

Christ — Our Pascha is the Catechism of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the largest of the 23 sui iuris Eastern Catholic Churches. It was first published by the Synod of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Ukrainian in 2012 and in English in 2016. You can read it on the left or download it here. Below is a review by The Revd Mark Woodruff, from the Pascha & Pentecost 2017 edition of our twice-yearly review, Chrysostom.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), the largest of the churches of Byzantine Rite and heritage in communion with Rome, may be considered as enjoying a special position when it comes to preserving and promoting that tradition within worldwide Catholicism. Published in 2016 as the fruit of the work of a commission set up by the ruling Synod of the UGCC, its Catechism is primarily intended to form that Church’s own faithful, now present far beyond its heartlands in the worldwide Ukrainian diaspora, in the knowledge of the doctrinal, spiritual and liturgical heritage passed on from Greek-speaking Byzantium. Just as saints Cyril and Methodius transmitted this heritage to the Slavic peoples in the 9th century, so this English translation opens up a vision of it to a wider readership.

At multiple points throughout the text of over three hundred pages, this catechism displays its enormous pride in the wealth of the Christian heritage of Kyivan Rus’, from which the UGCC claims spiritual descent. Yet it is also at pains to show how that particularity in no way presents an obstacle to the UGCC’s awareness of its vocation within the Church Catholic, guaranteed according to its own self-understanding by its communion with the Roman Church, and through that Church to the churches of the West and the other Eastern Catholic Churches.

Latin Rite Catholics and others, often unaware of the diversity of traditions present in worldwide Catholicism, might wonder why the UGCC needs its own Catechism at all. The introduction makes it clear: not only does the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) itself express the hope that it will be complemented by local catechisms sensitive to the needs of local churches, but Pope Saint John Paul II recalled that Eastern and Western traditions often express the same truth in different ways that are to be considered as complementary rather than in conflict. The introduction quotes the late Cardinal Lubomyr Husar, revered by UGCC faithful as their patriarch, who expresses the same conviction: “the theological understanding of divinely revealed truths can be different in various cultures, just as liturgical rites are different” (Christ — Our Pascha, p. xix, quoted from late Patriarch’s introduction to the 2002 Ukrainian translation of the CCC.)

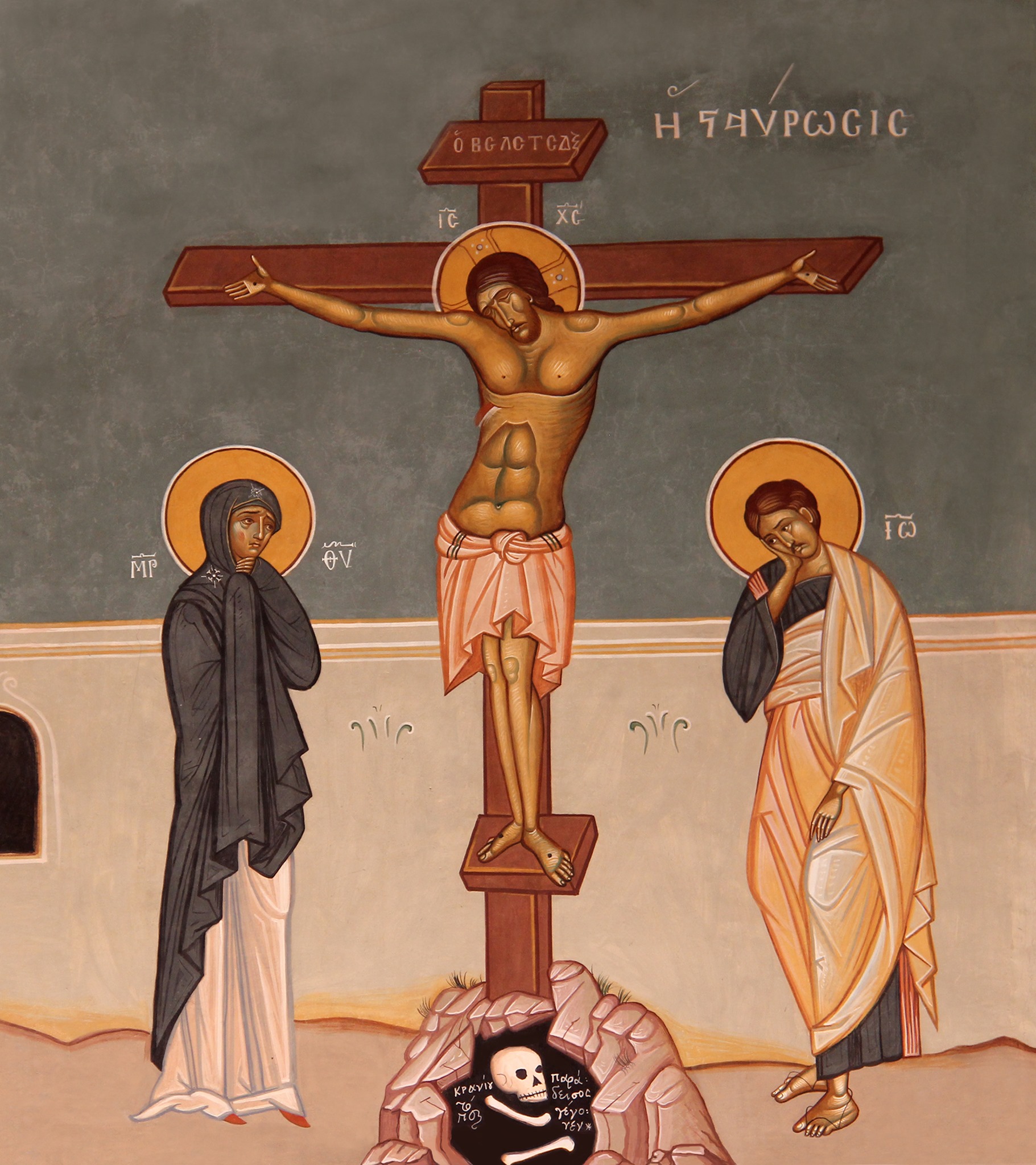

This catechism’s commitment to that principle of presenting the common faith of the whole Church within the theological language and method of its own tradition is evident not only from the manner in which it treats individual doctrines but above all in its overall structure and perspective. The title itself Christ — Our Pascha sets out that programme succinctly. First of all the approach is resolutely Christocentric, setting out the entire panoply of Catholic teaching on God as Trinity, the economy of salvation, the Church, with its sacraments, worship, prayer and ascetical and moral striving, in relation the incarnation of the Son of God. The reference to the paschal celebration, whose absolute centrality is so firmly anchored in the consciousness of all Eastern Christians, makes it clear that the teaching contained in the catechism is not the fruit of abstract speculation but of concrete experience of the central event of salvation history and of the multiple ways in which the risen life of Christ unfolds within the historical existence of Christ’s ecclesial Body.

Christ — Our Pascha sets out the articles of the Creed, the saving mysteries of Christ, the nature of the Church and its sacraments, the liturgy and the prayer of the Christian, and the demands of life according the commandments of God, before concluding with the eschatological consummation of all things in Christ. In this respect it is like the CCC, but there are also differences which, if we remember that they are complementary, not only show us how the Byzantine approach is different but also that it can offer useful considerations for dialogue between the two traditions.

Thus, it is noteworthy that whereas the CCC starts with a lengthy preamble concerning the sources of revelation and the modalities of the human response, Christ — Our Pascha plunges straight into the content of the credal confession. I think this flags up from the outset a difference brought about by the historical developments which caused the Western Church, confronted by the successive challenges of the Reformation and the Enlightenment, to become overly preoccupied with the mechanism of the transmission of the Apostolic Faith in a way that has been detrimental to the primacy of its content. The East continues the older approach of proclaiming doctrine as something which validates itself and seeing the Church’s historical definitions — in councils and through theological reflection in tandem with the quest for personal holiness — as something necessary but secondary. In other words, Church authority emerges from the content of the Faith, rather than the other way round. Arguably, this means that individual Faith is seen as a response elicited by the attraction of the concrete life of the Church rather than as submission to an external authority.

The notion that the Faith received from the Apostles is something lived out in the Church before it is contained in doctrinal formularies is borne out by the space given by Christ — Our Pascha to the concrete expression of that faith. Right at the outset, the Anaphora of Saint Basil, with its beautiful rehearsal of salvation history, is presented as a foundational text alongside the Nicæno-Constantinopolitan Creed. It comes as no surprise, then, that more than a hundred pages of Christ — Our Pascha are devoted to the liturgical life of the Church, explaining in a way that is both complete and succinct not only the dogmatic truths about what the Church does but also the way they are expressed in practice. The Byzantino-Slavic tradition is explained through its services, chant and iconography. The CCC in comparison gives a more theoretical account of the sacraments and sacramentals, perhaps reflecting the sad fact that in the West liturgical life has too often been conceived as a screen on which to project the theological preoccupations of each age rather than as being itself a privilege expression of the Faith from which we must learn. Christ — Our Pascha, in presenting the liturgy as itself a means by which the Faith is passed on from the Apostles through the Fathers, masterfully applies the celebrated axiom of Saint Prosper of Aquitaine “the law of prayer should establish the law of belief”. Similarly, Eastern Christians, whether or not they are in communion with Rome, will be on familiar territory when they discover that an important part of Christ — Our Pascha is given over to ascetical teaching, such as the importance and meaning of fasting. Christian life is presented as a combat against the passions to restore the divine image in the human being through divinising union with Christ in the Holy Spirit, and this struggle provides the necessary context to moral teaching which can otherwise be seen as an arbitrary set of rules. One section is inspiringly entitled “Christian morality as a liturgy of life”. Many a Western Christian might find this section more thought provoking, perhaps even challenging, since ascesis, when it has not been abandoned altogether, has been increasingly separated from morality in the West.

Given the overall difference in approach, it is interesting to see how the theological issues which traditionally divide Catholicism from Orthodoxy are treated, since the UGCC believes that it has a vocation to live the traditions of Byzantine Orthodoxy in communion with the Western Catholic Church. While space precludes going into detail, it is interesting to note that on questions like the Filioque and papal primacy, the text of Christ — Our Pascha quotes sources from the common patristic tradition, leaving quotations from specifically Catholic sources like the Popes, Vatican II and CCC for the footnotes. In this way, it is possible to approach the controverted doctrines from the standpoint of a theological legacy common to East and West, and hopefully provide a contextualisation which may eventually be ecumenically fruitful.

From all of the above, it should be clear that I believe that Christ — Our Pascha has an interest which goes beyond the faithful of the UGCC. For them, it will be an admirable resource to deepen their not only their appreciation of the teaching of their Church, but enable them to participate more consciously in its life. For Christians of Western traditions, it can open their eyes to a vision of the Faith whose differences can be seen as complementary and which possesses a coherence and a grandeur that might offer much to their own, often somewhat restless quest for authenticity. For Orthodox, it might represent an invitation to go beyond contemptuous characterizations of “uniatism” and reflect on how far union with Rome might be compatible with fidelity to the patristic witness. The inevitable criticisms, if offered charitably and in good faith, might well be a helpful springboard for dialogue.

Since no human work is perfect, I will offer a few small criticisms of my own. A perusal of the index reveals inadequacies and even errors: it would have been useful if the subject references had distinguished text from footnotes; and paragraph numberings in the references are often out of sequence (e.g. the material referenced as para. 314 is given in fact at 313 — presumably as a result of an addition which has not been taken into account). At the level of content rather than realization, I would have preferred to read more on monasticism, given its importance in the life of the Eastern Churches, and perhaps some reflexion on how the traditional understanding of monastic life as the Christian ideal for all might be presented in a way compatible with the universal call to sanctity and the possibilities of achieving holiness in the world.

Overall, the unity of vision binding the Trinitarian Faith of the Church to the concrete search for holiness, understood as divinization through the Risen Christ and his gift of the Spirit, is the distinguishing mark of this catechism and its title to glory. It is of course also the glory of the Byzantine tradition as a whole, and to say that this book largely succeeds in its aim of presenting that tradition in an accessible way is the most fitting way to praise it. ✠