It is not May that is “Mary’s Month”, but Advent. And it is no accident that we keep today in its first week the feast of St John of Damascus – St John Damascene. Nor is it an accident that the Church provides for today’s Gospel the story of the blind men who see by faith (Matthew 9.27-31); but I shall come back to that.

It is not May that is “Mary’s Month”, but Advent. And it is no accident that we keep today in its first week the feast of St John of Damascus – St John Damascene. Nor is it an accident that the Church provides for today’s Gospel the story of the blind men who see by faith (Matthew 9.27-31); but I shall come back to that.

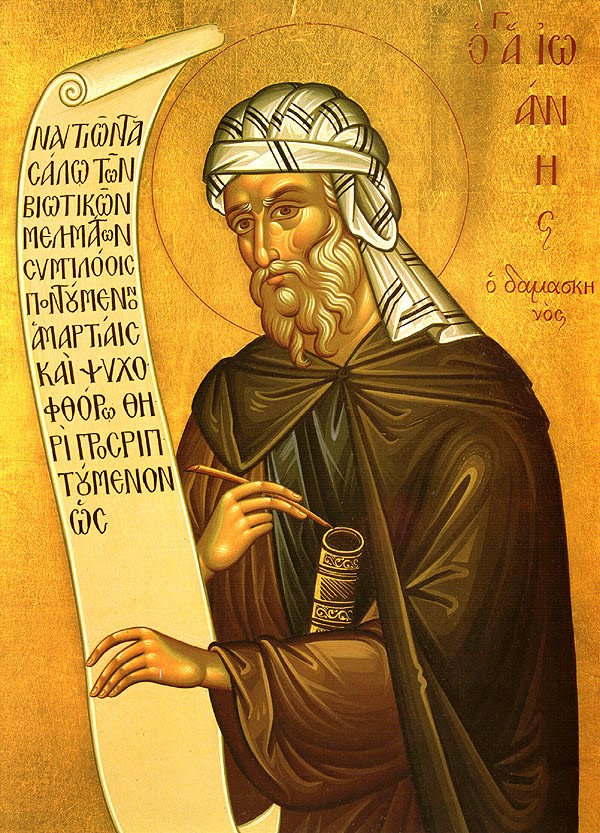

St John was a Syrian monk who had worked as an economic official in the court of the Muslim Caliph. When he entered the monastery of St Saba near Jerusalem around the year 700, he gave up not only earthly fame, power and influence in the empire of a relatively tolerant Islam, but also the wealth of his own Christian family. His Christian spirit of renunciation of worldliness will thus have been impressed by the absolute submission of the many Muslims he knew and worked with to the spiritual life, to God who is Spirit, to God who cannot – must not – be tied down to a merely human way of looking at things.

Too often, we think of God as simply a vastly larger version of us; so the way we imagine him actually diminishes him. (This is the spiritual blindness which today’s Gospel contrasts against.) Here St John – like all orthodox Christians – was at one with the Jewish people and the Muslims all around him.

But then he parts company with Islam, with Judaism and the “Puritan” tendency in Christianity. It was over the question of the veneration of our sacred images of Christ and the saints in this world, and our need for them as an intimate link to the mystery of the Incarnation of the Son of God, his taking real physical flesh right from in the midst of the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, truly the Mother of God.

A great controversy about all this disturbed the Church through much of the eighth Christian century; it has bubbled up occasionally ever since. It poses the questions whether it is right or wrong to depict Christ in his Passion on his Cross, Christ in his Power, the Mother of God and indeed any of the saints. Do these statues and icons not merely cut our God down to our size? Do they not merely make the great mysteries of the Incarnation and the Resurrection bite-sized? Do they not merely make the saints into objects of admiration and devotion at the level of basic fellow-human attraction? Should we not tear them aside as barriers to God in heaven?

No, says St John Damascene: it is essential that we have these images. They are not mere snapshots of people long dead, or events long past. They are there to make an impression on us in this world, from the life of the world that is beyond us. Did not Christ say, “The Kingdom of God is among you”? So it is with icons and statues and images. Behind and within them are the great cloud of witnesses, surrounding us, pressing on us with the life of heaven, making an impact upon us with the imminent reality of the Resurrection itself. Our eyes, which are for this world, may be blind to the world that is to come; but our faith sees what and who is bearing upon us.

So we cannot fail to speak to Christ’s image on the crucifix. We cannot fail to adore Christ making contact with us through the image of the Lord in his Power that you see in every Orthodox Church and many of our own too. You cannot fail to address the image of the Mother of God wherever you see her, holding her Son to us and bearing his life into our midst.

Rightly we love these images and pour out our prayers and praises, our griefs and hopes before them, not because we are deluded, but because they are evidence – hard, tangible evidence – that the Incarnation is more than an event in history: it is a fact of nature. God takes real, physical things and unites them with heaven, so that they can become holy in the world and thus conduct us into the next. In the same way, he took the humanity of the Virgin and united it with the Divine Nature of his Son. She is truly Mother of God, not only because of her relation to her Son and his work of redepemption on the Cross and the Emptied Tomb, but because she as Mother of the Church, is the instrument of our own union with her Son in that Church too.

Thus it was that above all St John Damascene defended the veneration of the image of the Mother of God. More than all the saints, it is she who brings through the icon and the statue this immediate, imminent presence of the Kingdom of God itself -it is in her womb, it is her very life. No saint can be considered “dead” or coming to us from the past. They are all participants in the Resurrection and above all it is the Mother of God, assumed into heaven, whose purpose it is to see us assumed into heaven’s Kingdom too, as she brings to us her Son with every glance of ours at her image and at every Advent, the true “Month of Mary”.

So with our Orthodox and Eastern Catholic fellow-Christians, in the words of a hymn for St John’s feast,

Let us sing praises to John, worthy of great honour,

the composer of hymns,

the stare and teacher of the Church, the defender of her doctrines:

through the might of the Lord’s Crss he overcame heretical error

and as a fervent intercessor before God

he entreats that forgiveness of sins may be

granted to all.

And may the Mother of God pray that this be so.

Fr Mark Woodruff

Vice Chairman of the Society